Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

—Robert Frost

At 6:21 a.m. on Wednesday, Jan 8, I opened my eyes to the blue glow of a digital clock,

which meant that I was in a motel, not at a campsite somewhere in the woods. The latter would have made more sense, given the smell of woodsmoke and fire.

I felt around for my contacts on the nightstand, sat up to put them in - my eyes were burning and dry - found my way to the window, and opened the blinds: complete and disorienting darkness. The sun wouldn't be up yet, but anywhere a motel is, there too are floodlights and neon, streetlights and headlights, the lights of cities and towns.

For the first time in months, I opened the maps app on my phone to see where I was.

At 6:25 a.m. on Wednesday, January 8, I woke up to the smell of a wildfire that was burning its way south toward L.A.

I jogged down the back stairs to the motel lobby and asked the desk clerk if I could store my bags with the desk for a couple of hours.

"I'm sorry," he said, looking genuinely sorry, "but we can't store luggage."

"All good," I said. "Is there a coffee shop around here? My truck's in the shop."

"There's a Starbucks across the street," he said. "But they don't have tables."

I laugh a little. "Efficient," I said.

The hotel had no coffee and no breakfast; the room was filthy, the shower didn't work, the sink had only hot water, and one night's stay set me back $212 I didn't have to spare. The day before, trying to kill time over an omelet and coffee at Denny's ran me a cool $31 with tip.

I thought of the Lyft driver who'd picked me up the night before. Looking at the address where I was headed, he asked, "Isn't that the Cockatoo Motel?"

"I don't think so," I'd said, looking up the confirmation I'd gotten from on some cheap-hotels-last-minute app. "It's the Candlewood Suites."

The driver had laughed. "I been in this town too long. Back in the day, that's what it was. It was in that film, too," he added, gesturing. "You know. Tarantino."

"Pulp Fiction?"

"That's it."

I'd looked out the window and watched one low-roofed walk-up fast-food place after another roll by.

The next morning, I thanked the hotel desk clerk and went outside. It was after sunrise but there was very little light; to the north, the sky was nearly black and thick with smoke.

A soft flurry of something blew into my face and caught in my lashes; I reached up to brush it away from my eyes.

Ash.

It was the third night in a row I'd had to scramble to find a room.

I wasn't even supposed to be in town. Had things gone according to plan, I would have dropped off the truck for a minor repair on Saturday, flown LAX-ATL early the next day, picked up a rental car in Atlanta, driven to eastern Tennessee to get a dog on Monday, stopped off to visit one friend in Chattanooga and another in Alabama early Tuesday, and by Wednesday morning been rolling out of Memphis on my way to San Diego with a new dog riding shotgun in his brand-new upscale console booster seat.

Instead, the dealership where I'd dropped the truck for electrical work on Monday morning was stalling, inventing repairs I didn't need, ordering parts that weren't required, and getting jack shit done at the hilarious rate of $385 an hour.

I was stuck in L.A., and L.A. was on fire.

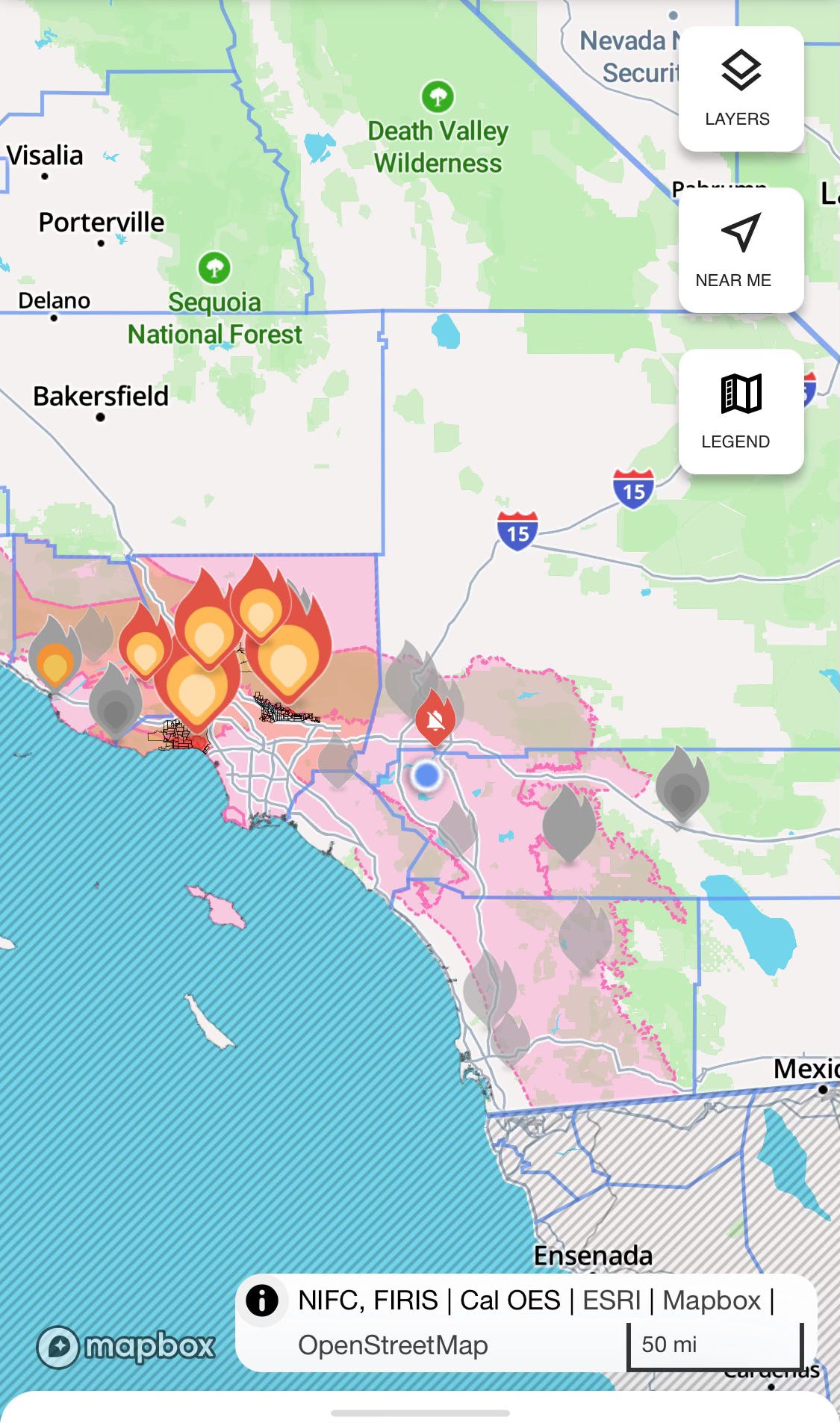

Early Tuesday morning, a brush fire broke out north of the city along the coast.

Unofficial reports at 10:50 a.m. said the fire was measured at about 10 acres and had been given a name: the Palisades Fire.

At 11:29 a.m., the fire was estimated at 200 acres, with zero percent contained. Evacuation orders for the area began. By midafternoon, at 3:23 p.m., more than 1200 acres were on fire.

Just after 6:20 p.m. on Tuesday, early reports of a second brush fire began to circulate; by 6:29, it had covered 10 acres just above the Altadena neighborhood. Less than half an hour later, the recommendation to evacuate was issued to the public; at 7:07 p.m., the blaze was christened the Eaton Fire, and at 7:12, the recommendation that residents evacuate was changed to an order.

Two days later—as I write this, late Thursday night—the Palisades Fire is approaching 20,000 acres and is six percent contained; the Eaton Fire has claimed five lives, nearly 14,000 acres, and is zero percent contained; more fires have started, some of which are up to 40 perecent contained, others not nearly so much; thousands of structures are damaged and thousands more destroyed; and the Santa Ana winds continue to blow.

Thirteen miles south of the southward-moving Palisades Fire,

in room 205 of the Candlewood Suites, I was putting drops in my eyes because I thought my allergies were going nuts and arguing with this fucking car dealership on the phone.

After two days of jerking me around, they told me that my truck wasn't operable because they'd taken it apart. I could either agree to pay $5000 in concocted charges or have it towed off their lot.

Another Emergency System Alert popped up on my phone as I wiped the corners of my eyes.

I told the guy to go ahead and fuck me sideways for repairs I didn't need, hung up on him, filed a complaint with the state, texted a friend, "Capitalism for the win," hit the lights, lay down in my clothes, and fell asleep watching live updates on the fires to the north, south, and east as they closed in.

Two weeks ago, in the mountains further north, I took a walk.

The path wound through a pine forest where the trees are sparser now that they once were, though I don't know when—there'd been a fire, not very recently, but recently enough that evidence of the forest's recovery was just beginning to show.

Heaps of blackened trunks and boughs that had been cut were scattered on the downslope. The stumps of trees cut back to thin the forest and make it less prone to fire were no longer raw and seeping sap, but barely healed, their rings still ridged to the touch.

The charred bodies of trees made me think of Dante's Inferno, of the circle of hell where souls are turned into trees on which the harpies eternally feed. A mile into a slow loop through the thin air I remembered it was one of the circles within the seventh circle. When Dante was getting down to the last few circles of hell, he lost the plot a little bit, maybe was rushed, started cramming vast categories of sin into a single circle. The seventh circle, for example, covers every varietal of violent sin. The harpies feed on the trees of the souls of those who commit violence against themselves, I was pretty sure; I tried to remember the other circles of Dante's Inferno, and by the time the walk was done I'd convinced myself there was—there had to be—a circle for those who commit violence against the earth, a circle for Man against Nature where Man is sent to hell for his sheer stupidity, for our violence and hubris and breathtaking wrong.

There isn't. I looked it up. There are other circles that apply, other places where the sin of human stupidity might fit.

There is the fourth circle—greed.

There is the fifth—anger.

The seventh, which does not have a subclause for violence against the earth, but which is for violence nevertheless.

The eighth circle is for fraud, which fits.

But maybe the ninth fits best: treachery. The inner sanctum of hell is reserved for those who betray. Dante may or may not have made much of a distinction between types or degrees of betrayal—based, for example, on the nature of the act, or the relationship of betrayer to betrayed.

It was afternoon, the winter light was thin and pale. Branches stripped of needles and leaves; blackened trunks with only a few boughs left. Several, too, where the fire had burned only partway up the body of the tree: charred at the base, you could trace the fire's path sometimes a dozen feet up, and beyond that, see the slender curled burn marks of flames.

And beyond even that, the branches, their needles thickening on branch and bough as they rose; and beyond that, the sky; and below my feet, the mountain itself, and below the thick carpet of needles, under the lingering smell, years since the fire, of smoke and burning pine, the tree roots burrowed still deeper into the slope, and when I stepped off the trail and walked toward a ledge where I thought I caught a glimpse of something green, I crouched to peer at a stump that faced west, in full sun, and saw the youngest moss I've ever seen, growing in the crevices of the stump's exposed roots, and saw that the forest is still alive.

Early Wednesday morning, motel parking lot.

I bent toward the building, lit a cigarette, took two hard drags, body curled around the ember for protection, then put the cigarette out in the plastic cup of water I held. The air itself was harsher than a Pall Mall, sharp in the lungs, thick and heavy on the tongue.

A sudden gust of wind howled around the corner of the building, whipping sand and grit up from the asphalt into my face, shearing fronds and long strips of dry bark clean off the palms.

Then it fell still.

The near-empty lot was littered with trash, fronds, bark, bright shocks of magenta in the dim haze: somewhere nearby, a bougainvillea was bare, blooms stripped from her branches by the Santa Ana winds. They festooned the parking lot of a mostly abandoned motel, looking for all the world like the trampled favors and paper streamers and cheap glittery hats the morning after a party that went on too long.

Sirens. Then the distant sound of helicopter blades.

I began to understand that I needed to leave.

I took my phone out and booked the cheapest rental car I could find, walked back inside, and asked the desk clerk as I passed him, "Which route would you take out of town?"

I heard him call after me, "Take the 110. The 405 is already jammed" as I bolted up the stairs.

There's more to this story, but I'm in shock,

and it's taking forever to get this on the page and I don't know what it says and I can't get ahold of half the people I'm trying to reach in L.A. and the story doesn't matter anyway.

This isn't even the story. This isn't the story of what's happening on the ground, on the tens of thousands of acres that have burned and are still burning, in the neighborhoods and streets, in the lives of the people who've lost their homes and places of work and belongings, their livelihood and livestock and pets, the objects and places on which a history is mapped, the embodied stories of which we all consist, the living history of which we're all made.

A few weeks back, when I got started on this whole fire jag, after the walk in the half-burned forest and Dante's Inferno and the young moss I found, a passing exchange about Hemmingway brought Jack London's story "To Build a Fire" to mind.

I don't know why it's stayed there—the story—but it has. It's been smoldering ever since. I've woken to the smell of smoke, the taste of fire and ash in my mouth.

It's nearly 11 p.m. Pacific Time, Thursday, January 9th. Last night, as I crawled along in the traffic that clogged every road leading south and east out of L.A., breathing through a mask and watching the light from the fires that raged in four directions dance against the billow and plume of their own black smoke in the sky, I kept thinking about how my sense of fire has changed these past few years, because fires are different out here on the road, and so are the people, and so is their way of burning, and so are their reasons for building a fire.

The fires on the road aren't cozy fireplace fires, they aren't woodstove fires, they aren't even campfires. They aren't roasting marshmallows with the kids, or reading by firelight on a winter night, or pretending to rough it on a lovers' getaway in the woods.

They're a boy at an Arkansas campground building a fire in a tin can while he watches over his young wife asleep in their broken-down van that I've towed into my campsite because they can't afford to be there and I can't afford to leave.

They're Arturo at the Desert Trails RV Park south of Tucson city limits, who lives in the yellow trailer his grandfather left him and leans on his cane at a respectful distance and offers to go to the food shelf with me if I'm too shy to go alone.

They're the scattered fires in the desert dark along the unmarked border roads that make it look like earth and sky have changed places, and the fires on the ground are actually a dizzying cosmos of burning stars.

They're the skinny little rancid oil-smoke fire in a hubcap at one of those forgotten rest stops way off the main road.

I wonder how many of you have seen them; I wonder if you knew what you'd seen.

A flare up ahead in the lot; the eerie flash of eyes in your headlights, like you'd startled a pack of something wild. In the one-stall bathroom, you saw the sticker on the back of the door telling you in two languages the number to call on a phone you wouldn't have if you were being held against your will. You washed your hands, looked for paper towels that weren't there, walked back out into the night. You saw the contours of faces bent over the skinny little hubcap fire; maybe you noticed the group was all women, maybe not. Maybe you thought they were kids; maybe some of them were. You counted five of them, or seven, or 10.

There was one more. You couldn't see her, but she could see you.

The fires on the road are fires like these: a father has built a small fire for his family one night at the encampment of unhoused people that stretches alongside the freeway in winter. He puts the kids to bed, each in a nest of blankets and clothes under the tarp from which he's built a makeshift shelter against the wind. Outside the shelter, keeping an eye on his children, he lights a cigarette and waits for the embers of the fire to cool.

He leans back against his pack. Feeling himself begin to drift, he wills his eyes to open, shifts slightly so he doesn't fall asleep, and settles back again.

The hand that holds the cigarette twitches as he falls asleep.

The cigarette’s ember catches one bent blade of winter grass, then catches another. A small flame catches, creeps a few inches ahead; the flame finds its way to the edge of a torn piece of newsprint and flares.

The fire begins to move along the embankment like a thief.

It catches a bedroll, a backpack, a pile of trash, a bent and blackened spoon; it burns through a baggie, melts and twists a syringe.

The chemical stink from the junk wakes someone up. They stir, jolt upright, look around. They scramble to their feet, wake their children, call out to companions and friends.

Chaos, smoke, the stench of singe. A dog starts barking, a child begins to wail.

Down at the station, three firefighters are drinking coffee at the kitchen table while the rest of the crew catches some sleep. Dispatch crackles over the speaker: fire at the encampment off I-35.

The crew is in the rig and screaming down the north-south corridor through town and someone's saying Fuck, again? because they knew before they left what they'd find.

But wait; not yet. The crew hasn't even arrived. Don't look away.

Stop looking away.

Focus your eyes in the dark. Look closer at the lumpen shapes of bodies in makeshift shelters and tents, the faces of children and elders and people who have a couple hours at most to close their eyes before someone rousts them and tells them to move along.

The man needed to make something to eat for his kids, and he built a small fire to make it, and he only leaned back for a minute, and the kids went to bed with full bellies, and he just needed to rest.

Scan the dark. Look north, toward the city, and south, toward the road out of town.

See it? That flare, there.

Someone is building a fire.

Also, this essay is brilliant. Breathtaking.

Holy shit, Marya.

I have multiple branches of extended family out there. One was impacted by the Eaton fire—their home in Altadena was one of the only ones left standing because they stayed against evacuation orders. The other was as close as 15 minutes from the Palisades fire and she was waiting to see which way it would travel, ready to evacuate her apartment.

They described it as hellish and apocalyptic. I agree from the video footage they shared with us. The thing I've been thinking is it is not wrong or selfish for people out there, in it, to be thinking first about themselves and their neighbors, the people they know and share their lives with, in one aspect or another. That is common. That is community. There has to be something beyond one's dispensation towards "community" though, to see—REALLY SEE—the people _you_ see, the ones who deserve the same kind of care and concern as the ones who lost their homes and cars and lives but aren't even visible to most of the rest of us. This is why I follow you. One needs only to open their phone browser to see the images of these conflagrations. One needs to read what you are saying from the ground to remember that we are humans. I hope you have found a way to safety. And I hope you recover from your shock of events. My thoughts are with you. ❤️

I like how you casually snuck in that you're going to be getting another dog. Slick.